It was also the opportunity to catch up with an old friend we don’t see anything like enough. She joined us at the show and we went for a drink with her afterwards, which made the evening especially pleasurable.

The show is part of a tryptic with a series of BBC Radio 4 broadcasts (now available as downloadable podcasts, for free, and well worth listening to), along with a book, all credited to Neil MacGregor, director of the British Museum, who led the team that produced them.

|

| Hans Schlottheim's golden Mechanical Galleon or Nef moves around by clockwork, cannon firing |

|

| Tischbein's portrait of Goethe, recognised throughout Germany |

To make up for the gap in the exhibition, I’m going to tell one of the stories from the book and series but only hinted at in the show: the tale of the Jews of Offenbach.

Back in 1916, a magnificent Synagogue was opened in Offenbach, a suburb of Frankfurt. But on Kristallnacht in November 1938, when Nazi crowds attacked Jewish properties throughout Germany (crystal night because so many windows were smashed), the Synagogue was desecrated. By 1945, few Jews remained in Offenbach, mostly not German but from further east, and even they had little intention of staying, but were merely waiting for the opportunity to move on to the US or Israel.

By the fifties, however, the community there began to feel that they were obviously going to be around for a while longer, so perhaps they really ought to have a Synagogue again. At least for as long as they were still there.

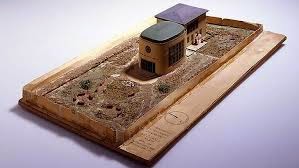

The authorities offered them their old synagogue back, but it was much too big, and had too many bad memories. So instead the municipality granted them a new plot of land across the street. The British Museum exhibition included a small architectural model of the buildings. Architect Alfred Jacoby told MacGregor “It was as far from the street as possible; it looks as if the architect squashed the building as far as he could to the back of the site.”

|

| The Offenbach Synagogue of the fifties: keeping well out of the way |

But Jews kept coming. One of them was Rabbi Mendel Gurewitz, who moved there from New York. He makes a telling point in the series: “There was a Jewish history, a very Jewish history, here in Germany, and it’s a shame just to decide, because of Hitler, they don’t want the Jews here any more, that you should completely close that country, close it for the Jews.”

Most of the new arrivals came from the East and, in particular, after the fall of the Soviet Union, huge numbers came from Russia. Some of the emigrants decided that Israel simply didn’t have the climate for them, so they came to Germany where, paradoxically, they felt at home – and above all safe. Germany has the most rapidly growing Jewish community in Europe.

Suddenly, the Offenbach synagogue, charming though it was, was too small. The community that decided to extend it wasn’t living in fear any more and felt no need to keep itself invisible. The new Synagogue is imposing and it fronts the street. “We are here,” it says, “this is our home, we belong here as much as anyone else.” And it’s beautiful.

|

| The Offenbach Synagogue as extended in 1998 A self-confident community, proud to be Jews in Germany |

You have a new multi-purpose hall, you have a kindergarten and so on. In fact our kindergarten is interesting because it is a completely interreligious kindergarten with a Jewish base. We have one third Muslim children, one third Christian children and one third Jewish children, yet children will all sit and sing Jewish festival songs and so on. It actually works.

Yes. It actually works. You can mix people with different faiths and have them do joyful things together, even the things of one of the faiths. Start with the kids and, who knows, one might set a pattern for life.

A feel-good story. About multi-culturalism. With Jews at the centre.

From Germany.

2 comments:

Amazing - I really want to visit! Great article :)

Post a Comment