If you enjoy reading crime novels, or watching thriller series, as much as I do, you must have been struck by a deeply suspicious pattern.

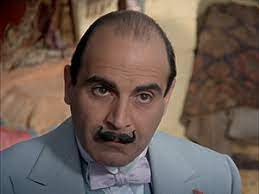

Wherever the super sleuth goes, there murders occur. Hercule Poirot, Agatha Christie’s favourite detective, has only to show up somewhere, even for a holiday in Egypt or on a train travelling across Europe, for someone to suffer a grisly, violent death. Of course, the detective then solves the whole mystery with extraordinary insight and convinces everyone, with apparently overwhelming evidence, that it’s all the work of someone other than himself.

|

| Poirot: crime sticks to him like unpleasant matter to a shoe sole |

Lock him up and the homicide rate would drop like a stone. Though that would mean there’d be fewer novels and series for us to enjoy. To say nothing of the reduced royalties for the writers.

It isn’t just the private detectives who worry me in crime stories. The police are no better. I mean, these guys are trained. They work to policies and protocols. So how come they ignore them so often?

A cop is standing outside a dark warehouse, at night, in a bleak and deserted district. You know what’s going to happen, right? Especially if the cop’s a woman, to get us feeling particularly stressed because we see her as somehow more vulnerable, though a cosh, to say nothing of a bullet, is just as damaging to a man as a woman.

Yup. She’s going to go in. Alone. And wander around in the dark with only a rather feeble torch to guide her. At some point, either she’s going to stand in a wide-open area with nothing protecting her back, so an assailant can take her by surprise from behind, or at some point we’re going to hear the clatter of booted feet running along a wrought-iron catwalk, and like a moron she’s going to go after the noise rather than sitting tight until backup shows up. Which surely her training would have dinned into her.

In fact, you only have to hear the words, “shouldn’t we wait for backup?” to know that she (or he) certainly isn’t going to. “I’m going in,” they say, or they go in anyway, jaw set, saying nothing at all.

|

| Alone in a sinister setting at night? Why wouldn’t she go in alone? |

There are certain set phrases. Practically cliches. Conventional statements that never mean what they seem to mean.

For instance, “we ought to phone the police”.

My thought is always, “yep. Good plan. You’ve just stumbled across a dead body that might incriminate you. Tell the police right now before things get a lot worse.”

But do they ever? Do they heck. Have you ever seen a series or read a book in which people come across a dead body in their house, their office, their car, and actually do phone the police?

Related to that one is the claim, “we have no choice”. No choice? Of course there’s a choice. You really could phone the police, you morons, before converting yourself into accomplices after the fact.

But, I suppose, the novelist – even some pretty good novelists – see no fun at all in that. So when someone suggests, “we need to get rid of the evidence”, don’t you just know that someone’s going to sigh and say “yes, well, I guess we have no choice”. So they’re going to do have a go, aren’t they?

You know, though, that it doesn’t matter how hard they try. A deep lake soon to freeze over in midwinter. A landfill site under thousands of tons of refuse. A mine deep in the mountains. It doesn’t matter, the cops will find the body.

Ah, well. I suppose the crime genre has its conventions, like all the others. Those narrative devices, used and re-used until they’re as threadbare as ancient traditions, are just their stock in trade.

What’s more, though I laugh at them, they clearly don’t bother me too much. After all, I keep reading and watching. And being just as entertained as ever.

Still, there’s crime and crime. And trying to get the reader or the audience to swallow this kind of implausibility is a bit of a fraud and a crime itself, isn’t it? Novel crime and serial crime, I’d be inclined to say.

No comments:

Post a Comment