That was back in 2012. According to Harris, Polanski told him that he’d wanted to for a long time but had never found the right way it. Inspired, Harris, author of major bestsellers such as Fatherland and Enigma, set to work at once.

The Dreyfus affair tore France in two in the late 1890s. On the one hand, there were the ‘anti-Dreyfusards’ who were convinced that a young officer, Alfred Dreyfus, convicted of espionage and drummed out of the French Army before being exiled to Devil’s Island off South America, where he was held in conditions close to torture, deserved his fate.

On the other hand, were the ‘Dreyfusards’ who believed that the conviction of Dreyfus was based on rigged evidence. Ultimately, they felt, it reflected the fear of a solid, Catholic and often royalist establishment that hated the changes that were being forced on French society and identified their source as the sinister figure of the ‘outsider’ – men such as Dreyfus, an ambitious Jew from a family that had the gall to be prosperous.

|

| An excellent novel and an excellent history |

Why a thriller? Harris tracks the painful process of establishing who had really been selling military secrets to the Germans. And still was, since one of the consequences of Dreyfus’s conviction was that the real spy was left free to continue his treasonable work. These are the elements of a great thriller, and Harris wrote a fine one while sticking closely to well-documented and closely researched historical evidence.

Why Picquart? He may not have been an anti-Semite but he certainly wasn’t particularly fond of Jews. But what he had was a powerful sense of justice and of his duty. An army officer, he was transferred into intelligence where he was tasked with tying up the loose ends of the framing of Dreyfus. But, unfortunately for his superiors, who went right up into the government, the closer he looked at the case, the more convinced he became that Dreyfus was innocent and a Major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy was the real culprit.

Picquart was subjected to pressure to the point of persecution. His liberty and even his life were threatened. But he battled on and ultimately Dreyfus was released while Esterhazy escaped into exile in England. He spent the rest of his life in Harpenden, just seven miles from where I live now. Though that’s not why we moved here.

As well as his novel, Harris also delivered a script to his friend in 2013. Polanski was delighted. Though the action was to be set in Paris, the financial conditions were better for making the film in Poland, so the director headed there in 2014 to start planning the film.

Sadly, as you know, Polanski has problems of his own, chiefly with the law back in the US over having sex with a thirteen-year old, in the scandal that led some to suggest he make a film to be called Close Encounters with the Third Grade. Once Polanski had travelled from France to Poland, the US authorities could launch extradition proceedings against him, which they promptly did. Eventually, the proceedings failed, but in the meantime the film project had suffered serious delay.

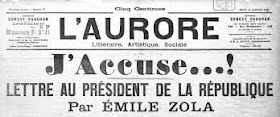

In the meantime, France had introduced new tax incentives for film makers. After further delays to wait for certain actors to be available, filming started in Paris this year and the film is due for release in 2019. Polanski changed the title to J’accuse, the famous headline printed above an open letter novelist Emile Zola wrote denouncing the case against Dreyfus.

|

| The celebrated headline over Zola's open letter to the French President, denouncing the anti-Dreyfusard conspiracy |

But because there is division, does this mean the truth is somewhere in between, in the middle ground between Brexiters and Remainers? Some might think so. But, in the Dreyfus case, was justice somewhere in the middle ground between Dreyfusards and anti-Dreyfusards?

The answer’s obvious. Dreyfus was not guilty of the charges against him. His treatment was indefensible. It even gave cover to the real criminal, Esterhazy.

There isn’t a half-way house, the sides are irreconcilable. You can’t release Dreyfus and keep him in prison. You can’t play a key role in Europe and turn your back on it.

Worse still, as we look back on the affair now, it’s clear the anti-Dreyfusards were driven by the worst of motives. They hated the Jew, the man whose presence in their army questioned their primal beliefs about the nature of France. They saw those who came to Dreyfus’s defence as despicable, because they put belief in the rights of man over the authority of the establishment and the grandeur of France. And they were happy to spread and believe lies to support their stance.

In the same way, Brexit has been based on lies deliberately spread and willingly believed. Brexiters are driven by hostility to outsiders, to those who arrive from abroad and work harder and often with more talent than they do. They must know, because after two years of debate it’s hard to deny the evidence, that there is no form of Brexit that will not leave Britain economically worse off than staying in the EU. But Brexiters are prepared to pay that price for the sake of ‘taking back control’, sometimes and revealingly expressed as ‘taking back control over our borders’, in other words making sure they can keep out people who look different or speak differently from them.

If only it were their economic wellbeing they were sacrificing to this goal. We live in a world in which the greatest powers are run by autocrats – Russia has had the authoritarian Putin in power for a generation, China’s Xi Jinping is turning increasingly dictatorial in a nation which is emerging as the great power of our century, and the United States has elected a narcissistic adolescent president once and may do so again.

What counterweight is there? Only Europe which, beset by populists and xenophobes, is struggling to maintain an oasis of democracy and human rights. And that’s the aspiration that Brexiters are setting out to undermine.

It’s not hard to imagine a film maker and a writer twelve decades from now turning their attention to the Brexit debacle. I think they’ll have little doubt that, like the anti-Dreyfusards, the Brexit camp got things desperately wrong because they were driven by base motives. Remainers, like Dreyfusards, fought a long battle for a more generous, more open and more equitable society.

At least, I can imagine that conversation if there is still a space in the world next century where liberal thinking is possible. Which I very much hope. Though I don’t think anyone can guarantee it.

No comments:

Post a Comment