I've no basis to claim that this is what it purports to be, a verbatim account of an outburst by Britain's eccentric Prime Minister Boris Johnson, but it ought to be and I thought that made it worth publishing.

|

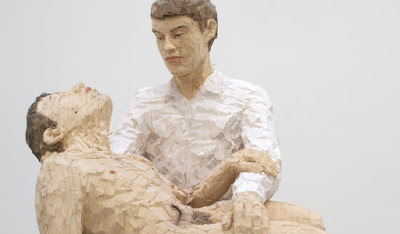

| Everyone’s favourite tousled imp Well, OK, not everyone’s... |

“No, no. Scratch that. No need for him to try the place. But he could shut the fuck up, seeing he has no idea what a shithole it is to live in.

“I mean. Bloody taxpayers give me only £30,000 a year to keep refurbishing the place. That’s hardly enough for one of our ‘red wall’ (ha, ha) voters to live on. Well, OK, maybe it’s as much as most people live on. Or, OK, if you insist, a bit more than most people live on. But to make Downing Street a home for someone with standards? £30,000 a year for redecorating’s just chicken feed.

“So, OK, I made my own arrangements. Without bothering the taxpayer. Which they ought to thank me for. And since I’m not bothering them, I don’t see why they should be bothering me.

“Actually, they’re not. I mean, most of the ‘red wall’ (ha, ha) voters aren’t saying a word. They may not like the way jobs are vanishing, or that salaries are heading southwards, and I haven’t done anything about all that levelling up rubbish Dom used to spout (serves the little shit right), but they look at my tousled hair and my impish grin, and they know they can’t hold anything like that against me. So they’ll vote for me anyway.

“After all, if they had my kind of connections and they thought they could get away with it like I always do, they’d do the same thing. They know that. I know that. They know I know it. We understand each other, in a way the middle-class Londonites in Labour can’t, and that makes a bond.

“So it’s only the gutter press making a fuss. Like the Guardian. The Independent. The Financial Times. And some opposition weaklings, though God knows I’m surprised they’re making so little of it. And those pinko so-called intellectuals at their Hampstead or even (yuck) Islington dinner parties.

“So what that I may have borrowed the money from the Tory Party? And it came from a named donor to the Party? I haven’t confirmed any of that. In fact, I’ve denied it. What gives anyone the right to doubt my word?

“Besides, even if I had done anything like that – and I’m not saying I did, mind – how’s that wrong? You think it might give that donor, if one existed, special access to me? Do you think I would have given him my private number, which I’m not confirming I did? What gives anyone the right to say that he might get privileged access to government, just because other people have got privileged access that way in the past? How can they claim that I’d do him any special favours, just because I’ve done special favours to people with my number before?

“You see why I don’t want to talk about any of this, like the chattering press keep demanding? ‘Transparency’? Who wants transparency? All that would achieve is to reveal that I’d engaged in some shady dealing, and I’m not confirming I did, which might lead people to question my integrity, and where’s the mileage in that?

“I mean, voters wouldn’t. I mean, not my voters. They never question anything. I can even shout and yell about letting their bodies pile high, by the thousand, and they don’t change they minds about voting for me. Why would they? After all, if they’re in a position to complain, they’re obviously not dead and with the body piles. So why should they care?

“Besides, the dead don’t vote. And there’ve only been a bit more than 100,000 British Covid deaths on my watch. Well, OK, quite a lot more than 100,000. But not quite 150,000. So even if you took all the bereaved into account, that can’t be more 500,000 people. With the kind of majorities we’re getting in the ‘red wall’ (what a joke), I can spare 500,000 votes. So, stuff it, I say.

“Voters don’t care about my wishing so many of them dead. Any more than they care about my dodgy dealings. Listen, we’ve just imposed anti-corruption sanctions on another 22 lousy foreigners. You want to do something about corruption? There you go. We’re doing it. That ought to be enough for anyone, without bothering about my own private arrangements.

“What’s that you’re saying? Anti-corruption ought to start at home? Like hell, my friend. Drives for standards start abroad. It’s charity that starts at home, and it’s charity to make sure that I live in decent comfort while I’m doing this job.

“You want to toss someone to the wolves for corruption in England? Help yourself. Throw that oik Cameron. Let him carry the anti-corruption can. He’s a perfectly unspeakable shit anyway, and he was stupid enough to get caught. He’s obviously the one to go down for it.

“Meanwhile, let’s just make sure I can live in the kind of dignity I’m entitled to. My loyal voters (ho, ho) in the ‘red wall’ (oh, I love saying that) would expect no less.”