“I don’t think about it, sir. That’s all sword-in-a-stone nonsense. Kings don’t come out of nowhere, waving a sword and putting everything right. Everyone knows that.”

Why, indeed, should we be that excited by the prospect of the King returning? What’s so wonderful about Kings? Charles I? He drove us so crazy we actually took his head off. Henry VIII? A tyrant whose reign so nearly 2000 executions a year, one in every 1500 people. Charles III, hovering int he wings? Hardly tyrannical, but hardly inspirational either.

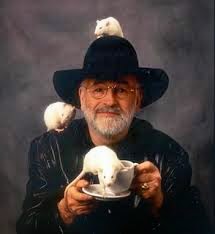

That’s what Terry Pratchett did so well, in more than achieving the programme he outlined to BBC’s Desert Island Discs in 1997: “I think I write – I hope I write – entertaining books that are good value for money.” Did I say achieving? He hugely overachieved it.

|

| Terry Pratchett: educating and charming us Sadly gone, but his voice and laughter live on |

I wrote it as an antidote to what I call the “belike he will wax wroth” school of fantasy. At that time, there was a lot of fantasy written by the people who had been influenced by the people who had been influenced by the people who had been influenced by Tolkien. And it was getting a little bit silly and everything was recursive and everything was feeding off itself and I just decided to create a world which was clearly ridiculous, designed to look ridiculous, but make certain the people reacted like people do in the twentieth century. That automatically became funny because they didn’t react like cliche fantasy characters, they had ideas of their own. Much to my surprise, what started off as a parody of fantasy became a fantasy series in its own right.

The exchange I quoted above, between the newly promoted Captain Carrot and Havelock Vetinari, Patrician, comes from the end of Men At Arms, one of my many favourites in the series. A little earlier, Carrot in his earnest enthusiasm for police work in the city, had expressed it rather neatly to Vetinari:

‘Do you know where the word “policeman” comes from? It means “man of the city”, sir. From the old word polis.’

‘Yes. I do know,’ replies the Patrician, who knows as much as Pratchett about words, and a lot more than Carrot.

Indeed, he makes the point himself at the end of their interview, calling Carrot back as he is about to leave the room.

‘You’re a man interested in words, captain. I’d just invite you to consider something your predecessor never fully grasped.’

‘Sir?’

‘Have you ever wondered where the word “politician” comes from?’

It does all us citizens no harm occasionally to remember that ultimately politicians and policemen are men of our city. However much, and however often, they may disappoint us.

Pratchett’s way of teaching such lessons without didacticism, and with a witty smile, appeared even in books ostensibly aimed at children. For instance, I shall wear Midnight.

I’m suspicious of the notion of evil. But the world today seems to be suffering from a level of cruelty it’s hard to call anything else. At its most extreme there’s the cruelty in action of ISIS, ritually beheading or burning its victims, even using a child to shoot one.

There is however a more indistinct kind of evil, a greyer cruelty, usually expressed in words (though who knows when it might turn to deeds). It’s embodied by such as Jeremy Clarkson believing himself entitled to bully anyone who irritates him; more seriously, it’s expressed by parties of the hard right (or even the ostensibly more moderate right) who casually inflict suffering on others not for what they’ve done, but for who they are: lone parents, gays, immigrants, the disabled, the ill.

Sadly, there are those who line up with the perpetrators of this evil. Jihadi John in Syria. The hundreds of thousands who backed Clarkson, preferring entertainment to the rights of employees not to be assaulted by a star. The millions who put their weight, and their votes, behind UKIP.

“… there are those,” writes Pratchett in I shall wear Midnight, “who would rather be behind evil than in front of it.”

True in the Discworld, and just as true on Earth. Pratchett’s answer is that of his central character, Tiffany Aching. When the moment comes in the novel that she lays down what needs to happen next, she even manages to get her audience laughing.

“That’s good, Tiffany thought; laughter helps things slide into the thinking.”

That’s Terry Pratchett. He has us laughing. And that slides things into our thinking. Things that need to be there.

Yesterday, a tweet appeared in Terry Pratchett’s account. It was from his own Discworld character, Death, who always speaks in capitals.

"AT LAST, SIR TERRY, WE MUST WALK TOGETHER."

A petition has been launched to ask Death to let us have Pratchett back. Well, it’s sadly unlikely to succeed. But at least his voice rings on among us. And for that, amid laughter rather than tears, we can be grateful.