What added spice to my most recent foray into the field was that it was conducted on Twitter. Debating the economic history of the last 80 years in 140-character bites is, frankly, challenging. Though no doubt my opponents would argue that my views don’t warrant much more.

Still, I’ve decided that I owe it to myself to take the slightly greater space a blog post affords to summarise my thinking more fully here. You, of course, by no means owe it to me to read on; however, if you do, I promise I’ll put in one or two funny bits before the end.

My potted history of the world economy over the last eighty years

There was a pretty ghastly depression in the 1930s. One of the worst ever.

A major step forward was taken when the US turfed the ghastly Republicans out. The incumbent was Herbert Hoover who gave his name to a dam. He was certainly a spectacular blockage to any kind of forward movement.

Alongside Roosevelt’s New Deal, a number of measures were put in place to ensure that no similar financial collapse would ever happen again. In particular, the Glass-Steagall Act included provisions to prevent the same organisation being involved in both investment banking and retail banking.

That makes sense since investment banking can lead to huge gains, but at the risk of massive losses. If only the money of wealthy individuals is involved, fine; if it’s the savings of millions of modest individuals, and the firms they rely on for a living, it’s not so smart.

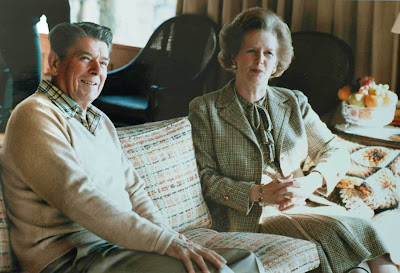

Now fast forward to the 1980s. The ghastly Republicans led by Ronald Reagan are back in office in the US, supported with poodle-like loyalty by Maggie Thatcher in Britain.

They listen to bankers, outstandingly qualified to brief them on economics, notably by virtue of having bankrolled their electoral successes. The bankers want a bit less constraint. Reagan and Thatcher confer. There’s been no great financial crisis since the Glass-Steagall Act, so what is it protecting us from? We might as well do away with all that red tape.

|

| As they sowed, so we are reaping. And weeping too. |

‘Don’t you take malaria tablets?’ my friend asked.

‘Well, I did for ten years, but I never got malaria so I thought I didn’t need them.’

Reagan repealed the relevant bits of Glass-Steagall. Thatcher brought in the ‘Big Bang’ in the city.

Released from their bonds, the bankers leaped exultantly into action. For twenty years they made fortunes and they paid themselves huge sums. What a great time they all had! As the guy I was arguing with on Twitter pointed out, ‘Big Bang was good for Britain.’ Measured by spiralling house prices, the number of Porsches on the streets and the amount of champagne consumed, that’s how it felt.

The nay sayers were, of course, saying ‘nay’. Even Alan Greenspan, then Chairman of the US Federal Reserve, warned against ‘irrational exuberance.’ But everything kept going well, year after year. And people don’t tend to think much further than a year or two. Few, apart from some of the better economists, realised that we needed to be reasoning in decades.

As it happens, two decades were all it took. The exuberance ended in 2008 when the present financial crisis blew up in our faces. The worst, surprise, surprise, since that of the 1930s. The smarter economists said it would end in tears, and here we were, crying.

How did I get into this argument? Because I criticised the present British government for trying to blame today’s banking scandals on the previous, Labour administration.

‘The recent scandals took place while Labour was in power,’ I was told. Which is true. But we mustn’t forget that it was Republicans and Tories who unleashed the bankers to wreak their worst on the whole of society.

The criticism that Labour deserves is that in office they did too little to re-establish effective regulation. It was hard, though. After ten or more years of huge apparent prosperity following the Big Bang, there was a powerful consensus that this was the way to build a stable, thriving economy. Labour wasn’t immune from that generalised belief.

Here’s an extract from a speech making clear how deeply ingrained that thinking was:

The Left advocated more intervention and government ownership. Those on the Right argued for monetary discipline and free enterprise.

Over the last 15 years governments across the world have put into practice the principles of free enterprise and monetary discipline.

The result?

A vast increase in global wealth.

The world economy more stable than for a generation.

The speaker ended by haughtily declaring ‘the debate is now settled’.

Who was the speaker? The then leader of the Conservative opposition, David Cameron. When did he make this speech? In September 2007. A year later, the crash burst on us.

And two and a half years later, God help us all, he became Prime Minister.

No comments:

Post a Comment