Imagine a nightmare scenario.

An underground network, run by a hostile organisation abroad, is conspiring to undermine your institutions, bring down your government and replace it with foreign, authoritarian rule that tramples on your most precious rights.

The conspirators aim to start with an assassination, at the very top of government. In fact, they’ve already tried, with gun or poison, and failed so far – gun misfires, that sort of thing.

The agents of the plot are everywhere, throughout society. That neighbour who seems so friendly, he could be one. He may be working hard to hand you over to a foreign dictatorship that hates everything you care about.

Sounds pretty dire, doesn’t it?

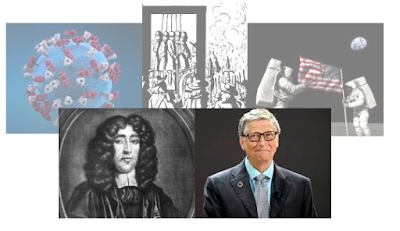

Or maybe not. You may well feel it’s just another conspiracy theory, to set alongside the notion that the Moon landings were faked, that 9/11 was a CIA plot, or that Covid-19 isn’t real, just part of a sinister ‘plandemic’. All fake news, you might say, fictions built on at most a grain of truth.

You’d be right. Except that I’m not talking about the ‘plandemic’ or the Moon landings. I’m talking about a far older incident, underlining the hoary truth that there’s nothing new under the sun.

Titus Oates was a strange man. Kicked out of schools, lying about being a Cambridge graduate to get into the priesthood, perjuring himself to take the job of a schoolmaster by falsely accusing him of sexually abusing a boy, kicked out of the Royal Navy as a chaplain for gay sex at a time when that kind of behaviour could have got him executed.

He lived in England at a time, the reign of Charles II in the late seventeenth century, when hatred of Catholicism was a constant background theme, that could burst out from time to time into something far more virulent. Which is what he engineered.

The conspiracy against our rights and values I was talking about wasn’t Communist, it wasn’t headed by George Soros or Bill Gates, it was claimed by Oates to be directed by the Catholic Church against England. He had managed to get enrolled in two Jesuit Schools, in Spain and in France, both of which he was kicked out of, and made out that he’d only gone there to spy for England on a Jesuit-led ‘Popish plot’.

He maintained that Catholic agents were planning on killing the King to precipitate a crisis in which the Pope could achieve his aim of bring England back under his control, wiping out Protestantism and installing a Catholic tyranny. Despite his unsavoury track record, Oates was able to persuade people to believe in him. Partly he was helped by his remarkable memory, enabling him to repeat the same entirely fictitious allegations, with perfect recall of the details, each time he was interrogated.

He also had excellent knowledge of intercepted documents giving information about the plot, though that was less extraordinary, seeing as he’d written them all himself.

|

| Conspiracy plots, fake news Perpetrators and victims |

He had plausibility, and his allegations emerged at a time when people were unusually ready to accept them. James, brother to King Charles and his heir, had converted to Catholicism. Charles himself was close to the Catholics, making him a dubious figures in the fight for Protestant values. That was especially true as he’d taken money from Catholic France in turn for extending more rights to English Catholics and, more significantly, joining a French war against Protestant Holland. When that war started to go badly wrong, the atmosphere was exactly right for the kind of bandwagon Oates got going.

The scandal lasted three years. It led to the execution of up to a couple of dozen innocent people before the allegations were all shown to be false. Then as now, fake news could gain widespread acceptance, as long as it was based on evidence that was plausible, even though it was false.

And, then as now, it could be extremely dangerous.

Why did I include the words ‘a distant mirror’ in the title of this post? It’s a reference to the historian Barbara Tuchman’s book, which used the terrible fourteenth century as a mirror to our own times. I’m not as ambitious as she was, but it did occur to me that we could do with one or two new mirrors from the past to view our own experiences more clearly.

Today, in the midst of the Coronavirus crisis, conspiracy theories are emerging again, as they did in the time of Titus Oates. And as then, they’re based on allegations which seem plausible but are generally false. They do, however, provide much the same benefits as Oates with his wild allegations.

They offer certainty, and cheaply, without any need for research or even detailed thought. A theory might suggest the pandemic was caused by Bill Gates, or George Soros, or the Chinese. It’s wonderful to have a pat explanation like that, rather than have to admit ignorance and keep looking. As H L Mencken pointed out, “For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong”. Conspiracy theorists want a shortcut to knowledge, and are just a little too lazy to check for themselves whether it’s true or not.

Secondly the conspiracy theorists, like Oates, offer us a scapegoat, and aren’t they wonderful? We’re not to blame for anything. It’s all down to Bill Gates, or George Soros or the Chinese. Just like in the 1670s, it was all down to the Catholics. Or in the 1950s, it was all down to the Communists.

An alternative explanation of what’s going on would require investigation, debate, careful thought. All hard work. And who wants to have to do any of that?

No comments:

Post a Comment