There are plenty of sad stories around in this time of pandemic and economic misery. So it came as no surprise when my friend Rosemary recently told me a sorry tale of her own.

Now Rosemary had been going through troubled times of her own, the details of which we don’t need to go into for the sake of this story. Let’s just say that as she flailed around seeking a solution to her difficulties, she came across a friend of hers who suggested that she might do worse than to consult a guru who lived up a nearby mountain.

“A terribly wise man,” she explained, “who always seems to have just the advice you need when you’re facing a serious problem.”

Well, Rosemary trusted her friend and, besides, she was running out of options. She decided it might be worth giving the suggestion a try.

“Where does he live?” she asked.

“In St Margaret’s hermitage, up at the top of that mountain,” her friend replied, pointing out of the window.

Where this was all happening isn’t terribly relevant to the story either, but you might have guessed from that last remark that it wasn’t central London.

|

| A hermit’s hut For a hermit with taste and the means to satisfy it |

“Oh, appropriate is his strong suit. The right word at the right time.”

And then her friend gave Rosemary a crucial piece of advice.

“The one thing to bear in mind is that, while he doesn’t charge for his services, he does expect a gift. It’s barren around the hermitage so he needs people to bring him supplies. Don’t bring food though – that’s what most people give him and he has plenty. What he needs is things to season the food he has. Salt, pepper, herbs, spices. Anything of that kind. He’ll be delighted if you bring him those.”

So Rosemary put together a large collection of every kind of herb and spice and seasoning she could think of, and stuffed them in her rucksack. Then she shouldered it early one morning and set off to climb the long track to the hermitage.

It was quite a trek. At first the path was clear and she followed it with ease. But later it became steeper and wandered from side to side. There were many others on the way to see the wise man, and sometimes she just followed them, but they didn’t always know the way either, so she would just find herself lost in company, which is a little better than being lost alone, but not a lot.

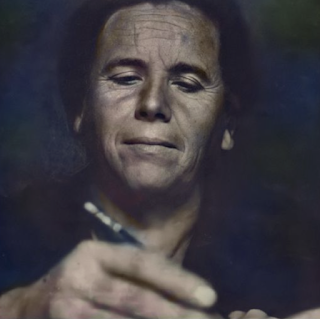

Eventually, she got to the hermitage, which was little more than a hut. It was already mid-afternoon, and she had to wait in a queue to be seen. Eventually, she was let into the hut, just as the sun was setting, knowing that a long return hike awaited her in the dark.

“Come in, my daughter,” said the hermit. “And what have you brought me?”

She proudly laid out her wares. Salt and pepper. A range of herbs. Many spices. Curry leaves. Coriander (OK, OK, my American friends, cilantro). Chillies. Enough to stock a fine kitchen.

“Where’s the parsley?” he asked

Alas, she’d brought no parsley.

“Parsley’s the one thing I long for,” he told her, obviously disappointed.

“I didn’t know.”

“Errors, my child,” he told her, in his wise way, “are merely moments crying out for correction, turning them into opportunities for improvement. Just come back another day with the parsley and I’ll answer any questions you may have.”

Her heart sank. A struggle back down the mountain in the dark lay ahead. Then a struggle back up again once she’d bought the parsley. With no guarantee that the wise man’s answer would, in fact, solve her problems.

You see what I mean about a sad story? Poor her. The hermit was adamant that until she’d brought him what he wanted, he wouldn’t pay any attention to her difficulties.

As she had no parsley for the sage, he gave Rosemary no time.

And here ends my little tribute to Simon & Garfunkel.