The thing about falling down a hole, is that it feels a lot less bad if you’ve been down it before and know the way out.

I spend most of my time these days preparing episodes for my podcast, A History of England (you don’t know it? You should check it out). Right now, I'm dealing with Charles I. He was a man entirely convinced that he’d been specifically selected by God to be King, so it was up to him to say what, if any, rights his subjects enjoyed, and he could withdraw them whenever he damn well chose.

That’s a pretty nasty hole and it took a dozen years of civil war to get out of it. But at least we know we found a way out.

That matters today, because we’re surrounded by men – I think it’s all men – who are certain it’s their calling to rule, and anyone who tries to stop them, must be guilty of treason or of rigging elections, or both.

Vladimir Putin knows that Russia’s welfare is his to protect. In his case, he’s the one rigging the elections, but that’s no betrayal, because he knows it’s only producing the right result anyway.

In Myanmar, General Min Aung Hlaing knows his country’s salvation is down to him, so when elections show otherwise, it’s obvious they’re rigged. Seizing power by force, as he has, isn’t just legitimate, it’s his duty.

In the United States, Donald Trump was just as certain that his nation needed him and him alone. Fortunately, the United States has a Constitution, and the will to preserve it, so Trump couldn’t in the end hold on to power by force, as the general has in Myanmar, though he certainly tried.

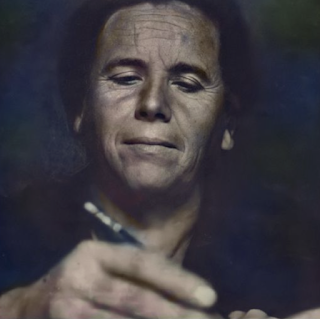

Applying Stalin’s principle that one death is a tragedy but a million is just a statistic, I thought I’d illustrate another of these dark holes with a story of one woman from one nation. A nation that fell badly but rose again.

|

| María Dominguez Remón |

To overcome these disadvantages, she taught herself to read. In her mother’s view, that meant too much time devoted to a non-feminine activity.

When she was eighteen, her parents married her off to a man twenty years older, who revealed a penchant for beating her up. Again, not the environment most propitious to achieving her life goals.

After several years, she escaped to Barcelona. It really was an escape: the law gave her husband the legal right to demand her return, and the police set out to look for her. But Barcelona’s big, and they didn’t find her.

Working as a servant, she was able eventually to put enough money aside to return to Aragon, with a machine that allowed her to earn a living making stockings. Somehow, she found the time to prepare for a teaching qualification, though she started work as a teacher unofficially, before qualifying.

Her husband eventually died, and she was free to remarry. She chose a far more congenial partner this time.

As Spain emerged from dictatorship and moved towards its second republic, she and her husband increasingly immersed themselves in left-wing politics. She submitted an article to the prestigious national newspaper El País, which duly published it. Before long, she was publishing journalism regularly in various political or local papers too. And she wrote poetry.

Although this had never been an ambition of hers, she also set a new record, as the first woman mayor in Spain under a democratic regime. It was only for a few months, but it gave her the opportunity to work on what she felt mattered most, extending education and reducing unemployment.

Her political ideas still resonate today.

Peoples become greater as the desire for conquest lessens in them.

The greatest deeds of the kings are written in history with the blood of their subjects.

Delete the word ‘patria’ (fatherland) from all dictionaries and you save humanity a great deal of blood.

Geography teaches that there are no fences marking the limits of the world’s circumference and yet man, in his pride, sets fences to his freedom.

Whites and Blacks are born under the same sun, so none should consider themselves superior to the others.

In 1936, a group of senior officers launched a military coup followed by a civil war that put Francisco Franco in power. She and her husband were both arrested, and some time in captivity – one dreads to think what captivity – they were murdered. She was shot in the cemetery of the town she’d served as mayor.

Franco, like Putin, Min Aung Hlaing, Charles I or Donald Trump, knew he had the right to seize power, and was prepared to torture and murder to take it.

María Dominguez disappeared into that particular hole of history. But, though the Franco regime lasted forty years, it too eventually end. Franco, like Charles I and Donald Trump, is now a bleak episode from which the country ultimately escaped.

Why do I mention Dominguez now?

Female remains have been found in that cemetery. The skull has been broken by a bullet from the back. DNA samples are being analysed, but it looks pretty certain that the remains are hers.

Today she’s honoured. A street has been named for her in Zaragoza, capital of Aragon. Documentaries and studies are being devoted to her.

Things were grim, but they can better. Not always for the individual, like Dominguez. But for the society which can at least remember her and relish the memory.

There’s some hope in that thought.

No comments:

Post a Comment