“Three be the things I shall never attain,” according to Dorothy Parker, “Envy, content, and sufficient champagne.”

Well, Irene Rodriguez isn’t going to provide me with sufficient champagne, or sparkling wine (‘champagne’ being a protected name), at least for now. Not, in fact, until she can replenish her stock. What she did give us, on the other hand, was one of the more magical winery visits I’ve ever enjoyed, as well as the tasting of a wonderful wine, not just good in itself but also reminiscent of my wife Danielle’s home region of Alsace, in Eastern France. That may not seem that extraordinary, until you consider that the visit took place in Northern Spain.

What’s more, that visit also gave us another insight into how the world of winemaking may at last be changing in its gender mix. It’s a hard world to break into, even for men, but far harder for women. It was a pleasure to read a recent article in the Guardian about how women are beginning to move into top positions in the highly conventional domain of Spanish bodegas (wineries).

The women in the article admit that success still depends a lot on contacts. You need to be born in that world or, like two of them, to have married into it. That made Irene’s case all the more encouraging, since she’s making her way in that field, without either belonging to or marrying into an established bodega family.

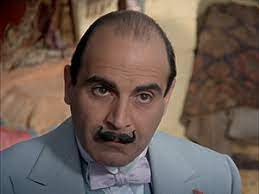

|

| Irene welcoming Danielle to her bodega |

Cantabria is a bit like that, except that it quite often doesn’t rain as much as it threatens. But it rains quite enough to ensure it deserves the epithet ‘green’. As a result, it’s a wonderful place to spend a holiday if you’re beginning to find that you can have too much of a good thing, with sun beating down and temperatures in the mid-thirties, as those of us who live elsewhere in Spain eventually do each summer. Cantabrian conditions make it ideal for white wine production, though getting a decent red with that much rain and relatively little sun, would be more of a stretch.

The region has been producing wine down the centuries, at least for as long as the only way of getting it from other places required haulage by horse and cart, which was excessively expensive. People who wanted wine drank Cantabrian until modern means of transport allowed wines from elsewhere to undercut local production, leading to its decline.

Lately, though, there has been a resurgence, mostly down to those courageous pioneers driven by their passion, who have made it their profession.

|

| Irene Rodriguez Fine oenologist, with one of her bottles |

As she points out on the web page of her winery, in the nineteenth century, every kitchen garden of her family’s village was planted with vines. Little by little, however, the vines were ripped out and replaced by other crops. Irene’s family chose to see if they could bring back the older practice and help revitalise the region’s traditions.

|

| Riesling grapes at Hortanza |

The vines are immaculately maintained, with hydrangeas and plots of lavender to add a touch of colour and complete a pleasing picture. The garden lies behind the modern and attractively designed winery and a row of three or four houses, one of them stone-built and belonging to the family too. They let it out to holiday visitors to help finance the operation.

|

| Dream back garden The holiday rental house is the stone building at the far right, the bodega building to the left |

From those grape varieties, Irene makes a wine that is rich in fruit flavours but with a refreshing edge in its dryness. While reminiscent of Alsace wines, it has its own strikingly distinctive character. A cousin rather than a sibling, and well worth savouring. We bought a couple of cases to enjoy with our friends and family.

She’s also started making a sparkling wine, but has sold out of her first year’s production. Such was the quality of the still wine that we’re looking forward to coming back again and trying the next batch of sparkling. A pretext, if any were necessary, to enjoy the cool of Cantabria in the summer next year too.

What’s more, the family has taken over another hectare of land a little distance away, already planted with Albariño grapes, the main variety of Galicia. That’s the province in the far west of northern Spain, best known for being the end of the Santiago de Compostela pilgrimage, but also as the source of a great many excellent wines. So that’s another pleasure to look forward to.

It was a lot of fun being shown around the bodega by Irene, who is as pleasant and easy to get along with as she’s passionate and knowledgeable about her profession. Tasting the wine just crowned the process.

Above all, though, we were delighted to meet a woman who has found her way into the exclusive world of Spanish wine production. And has done it with her own skill and dedication, starting small and building from there. I’m convinced she’ll do well, and it’ll be fun to watch her building on her success.

A great instance of a woman breaking through a glass ceiling by her own merits.

|

| Ready for sampling |