I never in my life saw a more noble or a more engaging aspect than his. He was dressed like those of his persuasion, in a plain coat without pleats in the sides, or buttons on the pockets and sleeves; and had on a beaver, the brims of which were horizontal like those of our clergy. He did not uncover himself when I appeared, and advanced towards me without once stooping his body; but there appeared more politeness in the open, humane air of his countenance, than in the custom of drawing one leg behind the other, and taking that from the head which is made to cover it.

The endearing rejection of convention – the refusal to bow or remove one’s hat – without displaying either discourtesy or unfriendliness was far from the most admirable of the Quaker’s qualities. Here’s the same writer’s view of the behaviour of William Penn, the Quaker founder of the colony of Pennsylvania:

The first step he took was to enter into an alliance with his American neighbours, and this is the only treaty between those people and the Christians that was not ratified by an oath, and was never infringed.

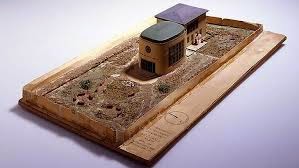

|

| William Penn, in the plain garb of a Quaker His agreement with Native Americans was unsworn, and unbroken |

However, it’s not for what they’re saying that I quoted these passages, however apposite they may be. It’s for the language they are in. For they were written in English, but not by an Englishman: they come from the pen of a giant of French writing, Voltaire, in his Letters on England.

It’s curious that one of the complaints I often hear from from Brits who’ve been abroad is that so few people out there speak English. This from people who often speak no language but their own. Still, it’s true that it remains amazing how few ever learn any other nation’s language. There are exceptions: in Copenhagen at least (I don’t know how things are in the more rural parts of Denmark) I was astonished not just by how many spoke English, but how well. That led me to feel that English was, for them, more of a second language than a foreign one.

Amsterdam is a city where I often feel embarrassed, at the way that the simplest people can understand and express themselves so easily in my language, though I can’t speak a word of theirs. I’m often told how many speak English in Germany, but I have to assume the people who tell me that haven’t been out in the countrysode much. It only takes a day or two in the Black Forest to realise that much of Germany remains strictly monolingual, or possibly bilingual, between High German (or “written German” as they call it) and the local dialect.

And then there’s France. Last autumn I was in a car hire office in Mallorca when my ears were assailed by a woman’s complaining in French about where she could find anyone who spoke her language. “I may be able to help,” I told her in her mother tongue, and she latched on to me as to some kind of saviour. The young woman behind the counter had been trying to explain to her that, while the staff were Spanish, they did all at least speak the recognised international language, English, but could hardly be expected also to speak the language of every foreigner who showed up in the place.

That seemed reasonable to me, but obviously not to the woman I proceeded to help out. In exactly the same way as most Brits, she clearly felt that the world had an obligation to speak her language, a possible result of belonging to one of the two great imperial powers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: British and French felt they could use their own languages to issue orders to other peoples and expect to be obeyed, if only because they had the bayonets and cannon behind them to ensure it happened. There may be a hangover of those attitudes still left in both nations.

Clearly, that wasn’t the case with Voltaire. He showed up in England in May 1726, having chosen exile as preferable to continued imprisonment in the Bastille: he’d had an argument with a thoroughly worthless but unfortunately noble young man back in Paris, who’d had his servants attack and beat him with sticks in the street; when Voltaire demanded justice of the authorities, he found no one would back him, a commoner, against an aristocrat; when he persisted in demanding satisfaction, he was thrown in gaol.

Funnily enough, his departure from England was little different. It’s not known exactly what he did, but it seems to have involved something like forging a letter of credit. As he left France to avoid prison, he returned to avoid the gallows.

|

| Voltaire: bright guy, though always in trouble And able to master a language other than his own |

It’s remarkable to me that it was initially in English.

We’re not all as talented as Voltaire, of course. We don’t all have the drive and the willpower he had to master a foreign language so thoroughly. But if international understanding starts with understanding each other’s words, as I believe it does, wouldn’t it be a good thing if we could at least aspire to imitate him?